The film “My Relatives Called Me Home” is a visual, oral tradition that communicates a gradual acceptance of the historical trauma the filmmaker experienced while researching the boarding school era from the late 1800’s through the early 1970’s. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Rosebud Sioux Tribe completed the ceremonies for the repatriation to their ancestral lands in South Dakota of nine children from the army barracks graveyard at the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Lynne Colombe’s journey documents both the return of the children’s remains from Carlisle Indian School and her own family connections and traumas connected to the boarding school past.

The Rosebud Sioux Tribe’s repatriation of the nine Carlisle children began a couple of years before the children were returned home. The Rosebud Sioux Tribal Youth Council and their organizers worked with the Rosebud Sioux Tribal Preservation Office long before the COVID-19 pandemic began, and dates were set for their return. Many other Tribes participated as the remains of the children were brought home between Pennsylvania and Rosebud Reservation — a journey of 1,400 miles.

Hundreds of Rosebud Sioux relatives and other Tribal relatives met these nine relatives Friday, July 16, 2021 at the Whetstone Landing in neighboring Gregory County. This landing was the meeting place for the boats that would carry the children to Carlisle. It was the last place their parents would see them.

This film was made in honor of the nine children who were returned home from Carlisle:

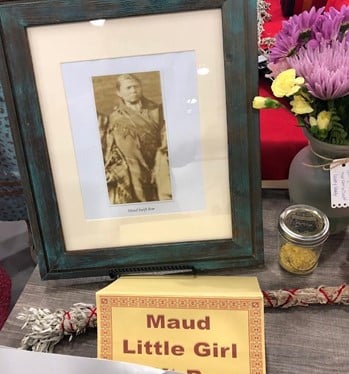

- Maud (Little Girl) Swift Bear

- Lucy (Pretty Eagle) Take the Tail

- Rose (Little Hawk) Long Face

- Kola (Friend) Hollow Horn Bear

- Dennis (Strikes First) Blue Tomahawk

- Alvan One That Kills Seven Horses

- Dora Her Pipe Brave Bull

- Ernest (Knocks Off) White Thunder

- Warren (Bear Paints Dirt) Painter

Personal Account of the Filmmaker

An enrolled member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, I began my research into the Carlisle children and learned that my own great-grandfather, William Colombe, was a student at Carlisle along with his twin sister, Minnie. My current research into a larger project places the Rosebud Sioux Tribal children’s count at 272 Rosebud students who attended Carlisle. As I continue to cross-reference census rolls from the late 1800’s, that number could rise. In a land treaty signed by my great-grandfathers Colombe, Roubideaux, and Bordeaux, there in those documents, Old Chief Crow Dog pushed the rhetoric into these land cessions council meetings that over 100 children had not returned to the Rosebud from off-reservation boarding schools between 1879 and 1904.

I often denied my own trauma before the pandemic, actually often claiming that I only carried, “2% of my ancestor’s trauma.” I denied this trauma because it was too hard to deal with the fact that I grew up without a maternal grandmother. As we repatriated the remains of these children, it became all too real that I was missing a huge part of my life: my connection with my grandmother. The actual loss of having that woman in your life to talk to, to confide in, to help you, to show you things, to teach you Lakota, to help you when your mother needs help — she was never there. My grandmother, Arlene Bordeaux, was in many ways herself, a person who did not survive boarding school.

Something that held me back from filming prior to Summer 2021 was thinking that I didn’t have access to state-of-the-art film equipment. But I finally just convinced myself to get out there with the camera that I have and one really good iPhone and start shooting. Sometime after this, as I began to work on a larger project with a loose scope, the Carlisle Repatriation events came into full swing almost simultaneously.

With my background in English and education, and then coming out of a short career in journalism, documentary filmmaking became my answer to create valid interpretations about my own world. Boarding School was something that I almost hadn’t wanted to deal with when I started out filming around the Reservation, because at that time, I thought that sometimes in “Indian Country” the word “trauma” is so heavily embedded with other things, that I didn’t want this concept of “damage,” “sadness,” “carrying forward of pain,” to be a part of my identity. But as I journeyed into the documentary work, the connection to my own relatives became impossible to deny.

In researching documentary films about the Lakota, I found that most of these films have three things in common: 1) Outside documentarians mostly see the poverty of the reservation, and they work hard to recruit our traditional people to dress up in their regalia and validate the filming they do during short periods of time that they spend on the reservations; 2) Off-Reservation and non-Native filmmakers are often allowed to be the “spokespeople” of Indigenous people — and I often attribute this to being the only culture left in America who are still treated as though we need translators for the “outside world” to legitimize our experience; 3) There seems to be a formula of Reservation Poverty in filming the Lakota, and these photographic shots must include (in any order): stray dogs, empty basketball courts, broken down houses, graffiti, wrecked cars and just anything gritty to highlight the fact that our Lakota Reservation is one of the top three poorest counties in the United States, almost always.

It was with all of this in mind that the journey to begin a film and work on even longer film projects like “My Relatives Called Me Home” started to happen. My journey is one of acceptance. I now understand my own historical trauma and where it comes from more deeply, and even though my grandmother, Arlene, is no longer with us on earth, I still feel a relationship with her — and all of my boarding school ancestors — through the interpretations of our own histories.

Mitakuye Oyasin. We are All Related. Wopila (thank you) and I would just like to add the following thank you to those at the end of the film: Thank you to Damon Buckley for his technical and photographic assistance and thank you to my daughter, Jaunie Marie Jones, for her animation of “Kicking Custer’s Butt.” Jaunie is 15 years old, on the autism spectrum, and has attended the St. Francis Indian School since the second grade. I would also like to thank my other two children: Kylee Wambli and Jocelyn “Carter” Colombe, for their support of their mom’s endeavors and their tolerance of her absence when filming and doing creative works.

Lynne M. Colombe is a documentarian, writer, humanitarian, and mother who resides on her home reservation of the Sicangu Lakota Oyate. She has formerly been a Native American secondary education teacher, educator, administrator, grant writer, and even Tribal School Board President/Vice-President (2017-2019). She is currently working on other films via, “A Room Without A View Productions,” which is a collective of tribal people and their allies who aim to create authentic, change-making Indigenous-led media. Once active in the NODAPL Movement at Standing Rock, Lynne continues to create a voice and challenge mainstream views on Native American issues both nationwide, and in her own Tribal community.

Teena Pugliese is a filmmaker and digital activist focused on stewardship and deep community with people and places. She loves working with storytelling, the arts and performance as pathways for healing and re-sourcing oneself. She is a youth media trainer, teaching a regenerative filmmaking process so others may tell their stories and reclaim control of their own narratives. She is inspired by and blessed to have worked alongside Indigenous communities since the NODAPL movement in 2016. She invites mindfulness into the filmmaking process with an intention to inspire heart full engagement and action in others. She has a BA in theatre with much “on the job training and experience” over the past 25 years and feels spirit full when singing and living truth fully on any stage. She is committed to and grateful for collaborations with all beings who work towards restoring our relations with each other.